Could Tech Bros Save Humanity?

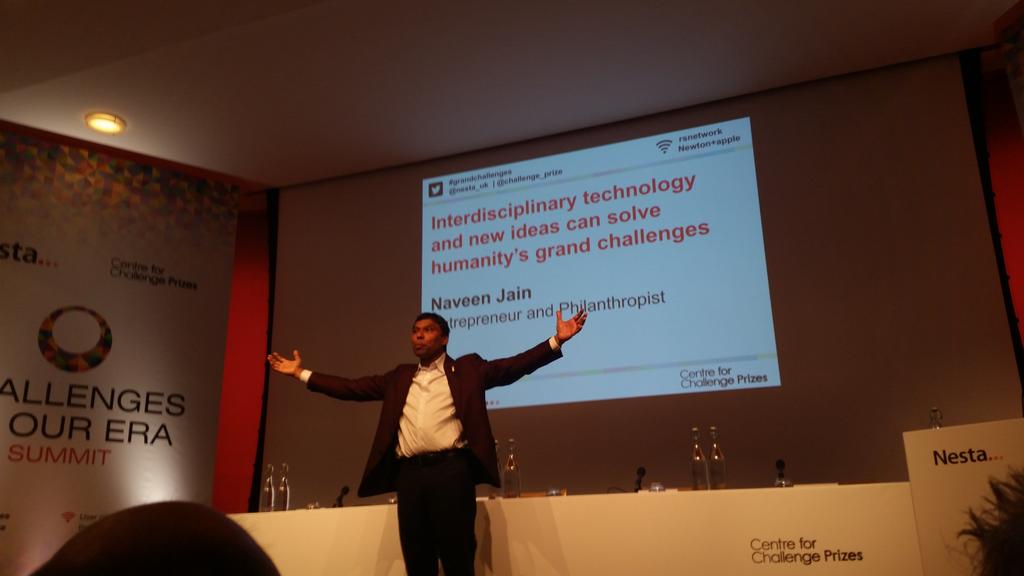

Naveen Jain, U.S. advisor to the Longitude Prize

By Joel P. Engardio

We can’t imagine life without our smart phones and apps. The downside is a proliferation of tech bros – a subset of tech workers who give their industry a bad name with each news report about entitled and jerky behavior.

Likewise, we rely heavily on prescription antibiotics for every sore throat and runny nose whether it's a bacterial infection or not. The downside is a proliferation of drug-resistant superbugs that threaten to kill 10 million people a year by mid-century, according to a recent British study.

What’s the connection? Imagine if the tech bros redeemed themselves by saving us from the superbugs.

The Longitude Prize promises $15 million to anyone who can solve antibiotic resistance. And the prize money for this medical problem is being dangled in front of Silicon Valley software engineers.

Why? The reasoning is that breakthroughs happen more often when innovators from another field use a fresh approach on someone else’s predicament.

“Thinking outside the box is not enough. You need to think in a different box if you’re going to solve big problems,” said Naveen Jain, the U.S. advisor to the U.K.-based Longitude Prize. “Experts in one field are limited by their own knowledge. They have a solution in mind as soon as they hear the problem. Their literal thinking only results in slightly better, incremental solutions. A non-expert thinks abstractly and interdisciplinary, which can be disruptive.”

Consider the XPrize team that created a novel way to clean up oil spills.

“There was a tattoo parlor guy, a mechanic and a dentist. It sounds like the start of a bad joke,” said Jain, a Seattle-based entrepreneur who also serves on the XPrize board. “But they came up with something twice as good as anyone from the oil industry. The tattoo guy had the idea, his mechanic friend figured out the operation and their dentist knew about drilling.”

The original Longitude Prize in 1714 offered big money for a way to measure longitude at sea. The British navy needed to safely navigate its global empire (latitude was easy, but longitude was vexing). While everyone expected an astronomer to win, a watchmaker solved the problem.

300 years later, the new Longitude Prize is also open to anyone with a winning idea. Today’s top concern is antibiotic resistance because we’re not doing enough to prevent a return to a pre-penicillin age.

Doctors continue to prescribe unnecessary antibiotics meant only for bacterial infections. Patients with viral infections don’t like hearing all they need is rest, especially when they have to pay for the visit. That’s why antibiotic prescriptions spike in the afternoon, according to the British study, when doctors are worn down by the day’s demanding patients.

Antibiotics are also used as a crutch when bacterial and viral symptoms mimic each other and it’s hard to tell the difference. So the Longitude Prize seeks to create a simple spit test that will determine on the spot if a bacteria or a virus is the cause of a patient’s illness.

But why is the prize courting San Francisco’s tech workers?

“If we can find a pattern in millions of samples of spit, then this is a software problem,” Jain said. “The answer might be in big data, genetics or nanotechnologies, which are all based in Silicon Valley.”

What about the bad press that paints tech workers as self-absorbed? Does Jain worry they won’t care, or that millions of dollars in prize money is the wrong incentive?

“Jerks exist in every field. So do good people,” Jain said. “Incentive prizes are the best mechanism because you only give money when the problem is solved. Philanthropy should never be about giving money. It should be about solving problems.”